A Chinese AI lab with 160 engineers, banned from buying top-tier chips, built a model that matched OpenAI's best — for roughly $5.6 million. That single achievement forced a $589 billion single-day wipeout of NVIDIA's market cap and triggered what venture capitalist Marc Andreessen called "AI's Sputnik moment." The DeepSeek story is not an anomaly. It is the latest and most dramatic confirmation of a principle economists have studied for decades: resource scarcity, when paired with ingenuity, does not constrain innovation — it accelerates it.

The implications extend far beyond artificial intelligence. From wartime laboratories to bootstrapped startups to mobile banking in Kenya, history shows that those who have the least often build the most. Understanding why — and how to harness this dynamic — is one of the most valuable strategic insights available to any individual, business, or organization operating under constraint.

The economics of "not enough"

The idea that necessity mothers invention is ancient, but its economic foundations are rigorous and modern. W. Walker Hanlon's landmark 2015 Econometrica study demonstrated the mechanism causally: when the U.S. Civil War cut Britain's cotton supply, textile manufacturers didn't simply suffer — they invented technologies to process inferior Indian cotton so effectively that prices rebounded to pre-war levels. Scarcity didn't just motivate a workaround. It permanently redirected the trajectory of technological progress.

Several theoretical frameworks explain why this pattern recurs. Joseph Schumpeter's creative destruction describes how resource-constrained newcomers, unburdened by legacy commitments, displace comfortable incumbents through radical innovation. Israel Kirzner's concept of entrepreneurial alertness adds a cognitive dimension: actors facing scarcity develop heightened sensitivity to overlooked opportunities, price differentials, and inefficiencies that well-resourced competitors simply never notice. Clayton Christensen's disruptive innovation theory completes the picture, showing that small entrants thrive precisely because they target markets too small or unprofitable for incumbents to bother defending — until it's too late.

The psychological evidence is equally compelling. Ravi Mehta and Meng Zhu's 2016 research across six experiments found that scarcity activates a constraint mindset that reduces functional fixedness — the cognitive bias toward using resources only in conventional ways. A meta-review of 145 empirical studies by Acar, Tarakci, and van Knippenberg confirmed the pattern: moderate constraints and creativity follow an inverted-U relationship. Some scarcity sharpens thinking. Too much paralyzes it. The sweet spot in between produces breakthroughs.

DeepSeek turned every disadvantage into an architecture decision

DeepSeek, founded in mid-2023 by hedge fund manager Liang Wenfeng in Hangzhou, China, faced constraints on virtually every dimension that matters in AI development. U.S. export controls banned access to NVIDIA's top-tier H100 GPUs. The team numbered roughly 160 people — compared to OpenAI's 3,500 and Google DeepMind's 6,000. Operating from Hangzhou rather than Silicon Valley, DeepSeek had no access to the global talent pipeline its American rivals drew from. Liang himself acknowledged: "We haven't hired anyone particularly special."

What DeepSeek did have was approximately 10,000 NVIDIA A100 GPUs stockpiled before the export ban, plus access to the less powerful H800 — a chip with identical compute power to the H100 but significantly lower interconnect bandwidth. Rather than treating this as a limitation, DeepSeek's engineers redesigned their entire architecture around it.

The results were extraordinary. DeepSeek-V3, released December 26, 2024, used a Mixture-of-Experts architecture with 671 billion total parameters but only 37 billion activated per token — drastically reducing compute requirements. Multi-Head Latent Attention, invented by the DeepSeek team, compressed memory usage by 93.3%. FP8 mixed-precision training, applied at unprecedented scale, roughly halved bandwidth requirements. A custom pipeline parallelism algorithm called DualPipe solved the communication bottleneck created by their inferior chip interconnects. Every major technical innovation traced directly to a specific hardware constraint.

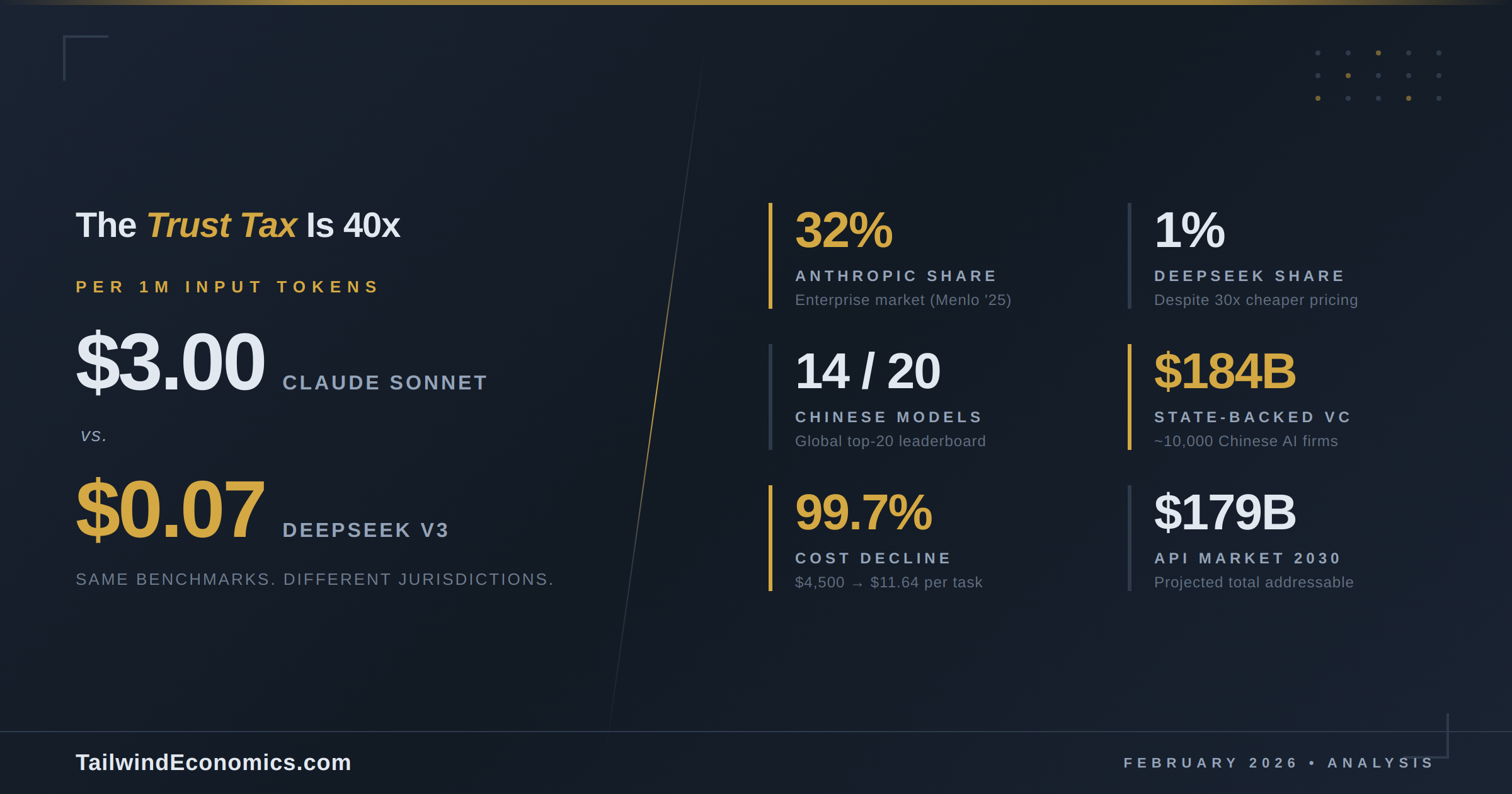

The model trained on just 2,048 H800 GPUs over two months at a reported compute cost of $5.6 million. Meta's comparable Llama 3 required 16,000+ GPUs and an estimated $500 million. DeepSeek-V3 matched GPT-4o and Claude 3.5 Sonnet on most benchmarks and outperformed them in mathematics, scoring 90.2% on MATH-500 versus GPT-4's 74.6%.

Then came DeepSeek-R1 on January 20, 2025 — a reasoning model built atop V3 using reinforcement learning at an additional cost of roughly $294,000. R1 matched or exceeded OpenAI's o1 model across multiple benchmarks, scoring 97.3% on MATH-500 versus o1's 96.4%. It was released under an MIT open-source license. Within a week, the DeepSeek app overtook ChatGPT as the number-one free download on the U.S. App Store. On January 27, NVIDIA shares fell 17% — the largest single-day market cap loss for any company in U.S. stock market history. The Nasdaq shed roughly $1 trillion. Andreessen's "Sputnik moment" label stuck.

Time as a weapon and the small player's structural edge

DeepSeek's story illustrates a broader strategic principle: when resources are scarce, time compression becomes the primary competitive weapon. Eric Ries's Lean Startup methodology, itself inspired by Toyota's post-WWII resource constraints, formalized this insight. Build-Measure-Learn cycles shrink the cost of experimentation. Minimum viable products replace exhaustive planning. DeepSeek embodied this: a flat organizational structure with no hierarchy, flexible GPU allocation without managerial approval, and a culture where a junior researcher's personal interest could produce a breakthrough like Multi-Head Latent Attention.

This pattern of constrained speed defeating resourced incumbents repeats across industries. WhatsApp served 450 million users with just 55 employees and 32 engineers before Facebook acquired it for $19 billion in 2014. Mailchimp took zero venture capital while competitor Constant Contact raised over $100 million — then sold for $12 billion. In Kenya, M-Pesa launched mobile banking on basic flip phones costing under $10, lifting 194,000 households out of poverty and increasing financial inclusion from 26% to 84% in fifteen years. Each case followed the Christensen playbook: small players targeted markets incumbents ignored, built lean operations around constraints, and scaled before the establishment could react.

Wartime innovation offers perhaps the starkest evidence. Facing material scarcity and existential urgency, Allied scientists prepared 2.3 million doses of penicillin for D-Day — compressing what would have been decades of pharmaceutical development into months. U.S. factories produced 800,000 tons of synthetic rubber by 1944 after Japan's Pacific conquests cut off natural supplies. Constraints didn't slow the war effort. They catalyzed an industrial revolution.

The caveat: scarcity alone is not sufficient

Intellectual honesty demands acknowledging limits. DeepSeek's $5.6 million figure covers only the final training run — analysts at SemiAnalysis estimate total infrastructure investment closer to $1.3 billion. Liang Wenfeng's hedge fund provided the financial runway. His team, while small, consisted of highly trained researchers from China's top universities. The Acar meta-review's inverted-U finding is critical: extreme deprivation without a baseline of knowledge, talent, and strategic focus produces paralysis, not breakthroughs. Scarcity is a catalyst, not a substitute for capability.

As economist Matt Clancy argues, "Invention has two parents — necessity and knowledge." DeepSeek succeeded not because it lacked resources, but because its constraints were moderate enough to sharpen focus while its team possessed the expertise to channel that focus productively.

What constrained actors should actually do

The evidence points to concrete strategic principles. First, audit your constraints honestly — identify which limitations can be converted into architectural decisions, as DeepSeek converted chip restrictions into efficiency innovations. Second, compress iteration cycles ruthlessly. Flat hierarchies, rapid experimentation, and lean methodology turn time into your strongest advantage against slower, better-funded competitors. Third, target the gaps incumbents ignore. Christensen's asymmetric motivation means large players will rationally cede the markets that matter most to your survival. Fourth, open-source strategically. DeepSeek's MIT licensing attracted global developer adoption and talent — a force multiplier no marketing budget could replicate. Finally, recognize the inverted U. Pursue the constraint mindset deliberately, but ensure your team has the minimum knowledge base and resources needed to execute. Scarcity sharpens the blade. But you still need steel.

Conclusion

The DeepSeek episode was not a fluke — it was a theorem demonstrated at scale. Across centuries of economic evidence, from Schumpeter's gales of creative destruction to Mehta and Zhu's laboratory experiments on constraint mindsets, the finding is consistent: moderate scarcity, paired with talent and urgency, produces disproportionate innovation. The $320 billion that big tech plans to spend on AI infrastructure in 2025 may build impressive data centers. But if history is any guide, the next breakthrough is more likely to emerge from a team that has less — and therefore must think differently.