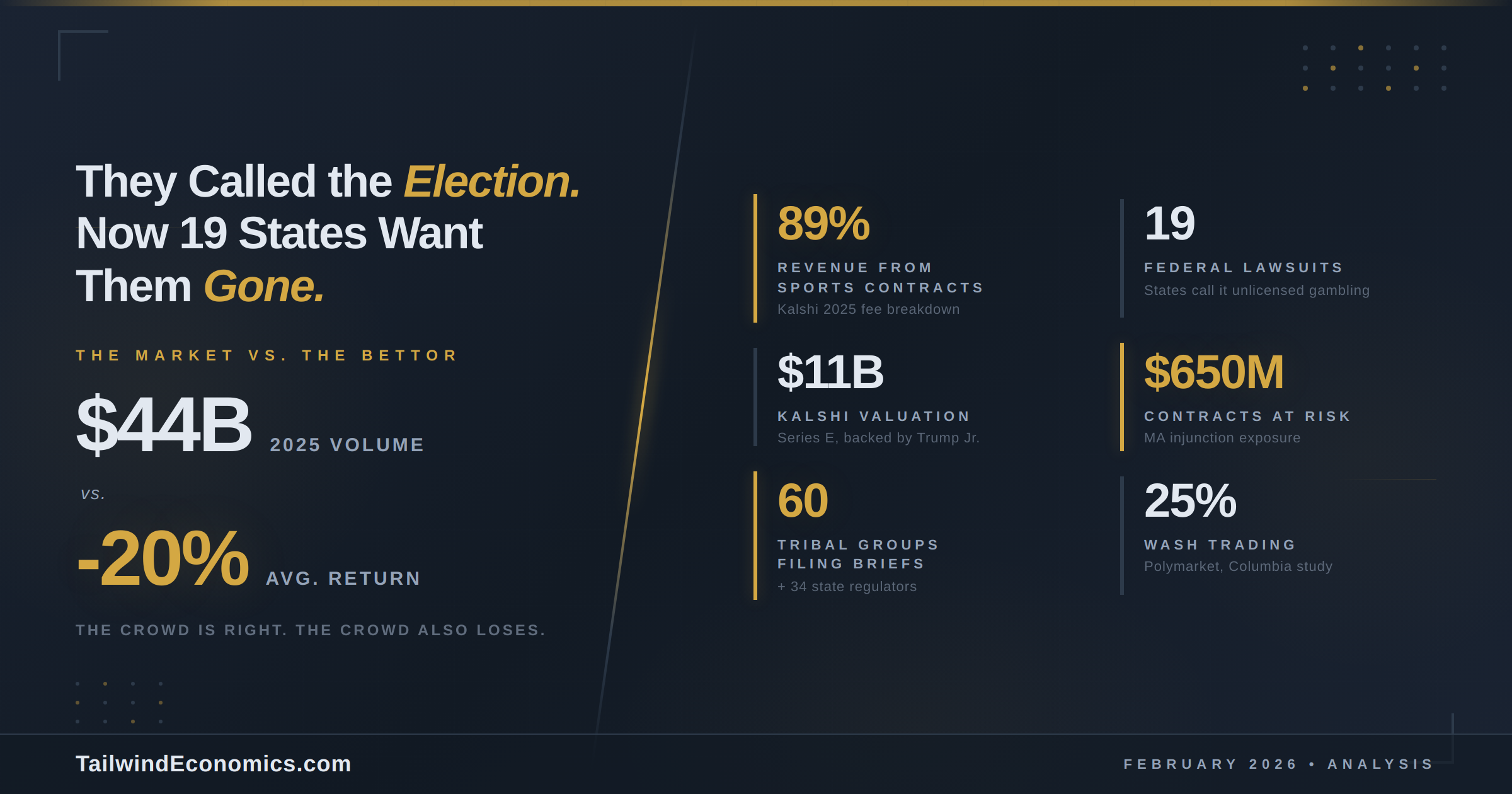

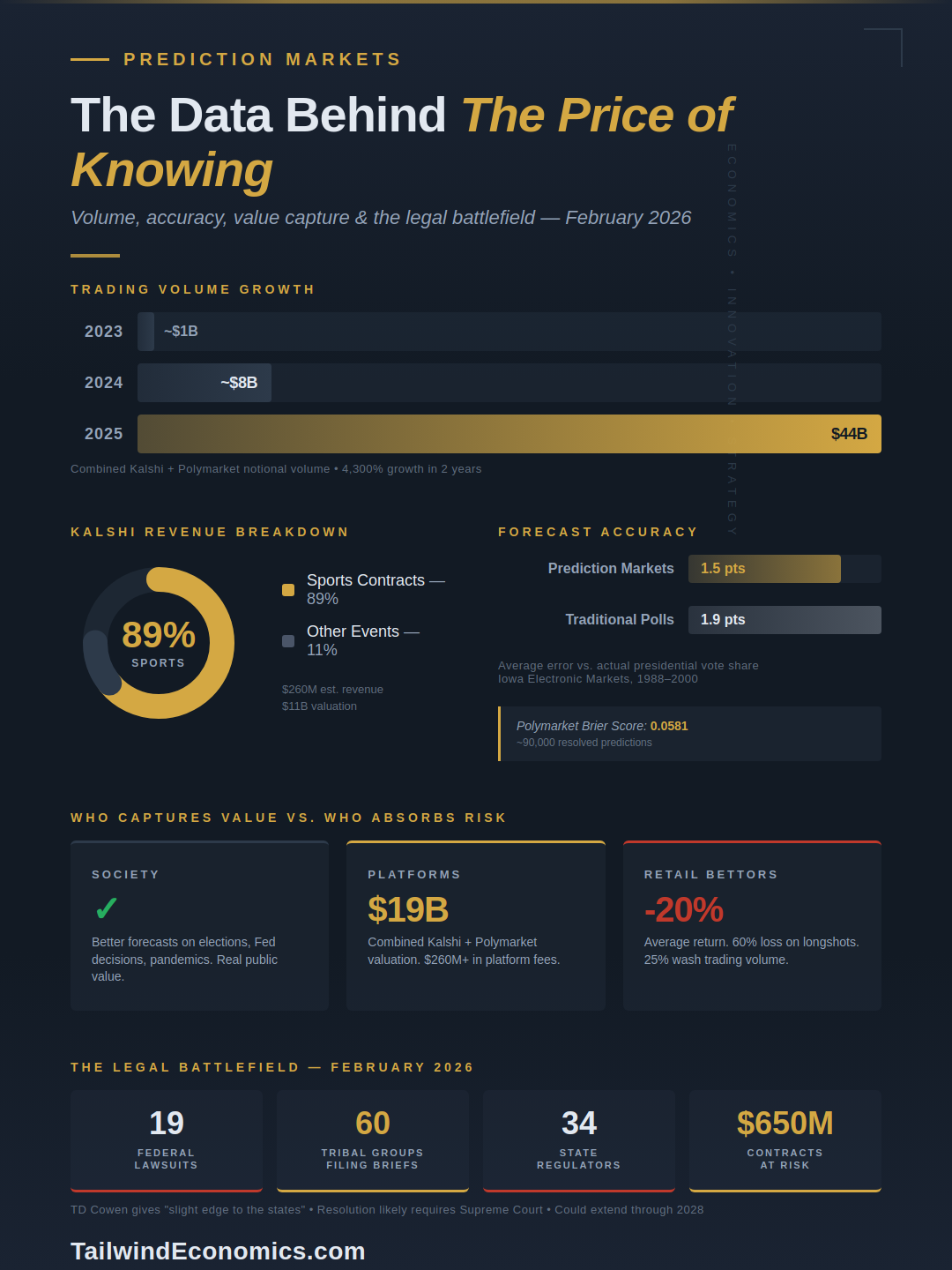

Prediction markets have evolved from an academic curiosity into a $40 billion industry that is forcing economists to reconsider fundamental assumptions about how information moves through society. Kalshi and Polymarket — the two dominant platforms — collectively processed roughly $38–44 billion in notional trading volume in 2025, a staggering expansion from barely $1 billion two years prior. Their most provocative achievement came in November 2024, when both platforms signaled a decisive Trump victory while polling averages and mainstream forecasting models called the presidential race a coin flip. That single data point has reshaped regulatory attitudes, attracted billions in venture capital, and ignited a deeper question: are prediction markets the purest expression of economic theory we've ever built — or a sophisticated casino dressed in the language of Friedrich Hayek?

Hayek's 80-year-old idea finally gets its laboratory

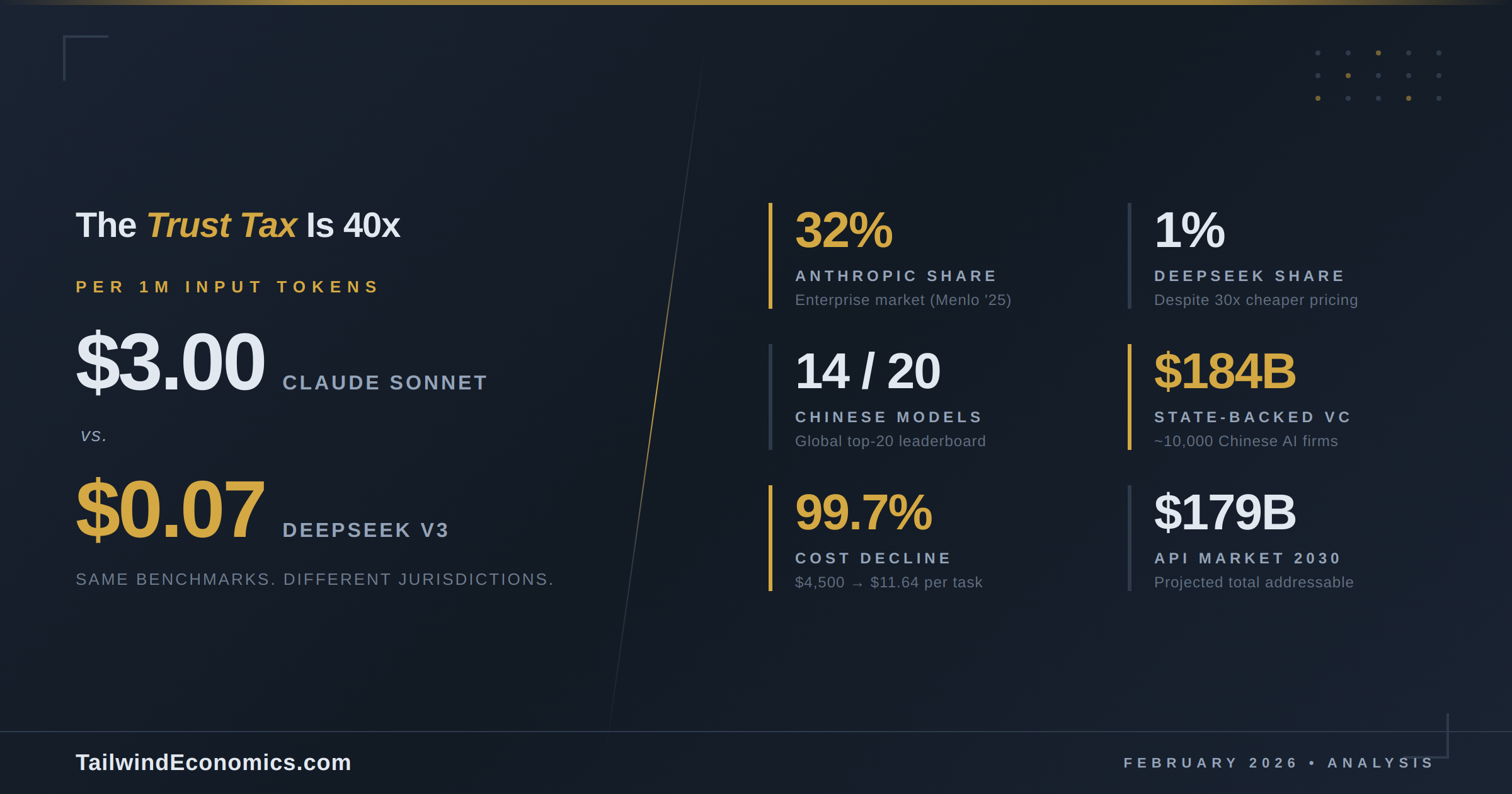

In 1945, Friedrich Hayek argued in The Use of Knowledge in Society that the central economic problem was not resource allocation per se, but the aggregation of knowledge "dispersed among millions of individuals." No central planner could gather it. Only price signals could. Prediction markets operationalize this insight with startling directness. When a trader in São Paulo buys a contract on the Federal Reserve's next rate decision and a hedge fund analyst in London sells it, the resulting price synthesizes information neither party fully possesses. CFTC Chairman Michael Selig explicitly invoked Hayek in January 2026 when announcing new rulemaking to formalize prediction markets, describing them as mechanisms for "aggregating dispersed information" — language pulled nearly verbatim from the 1945 paper.

The empirical results are compelling. Iowa Electronic Markets data spanning 1988–2000 showed prediction market forecasts landing within 1.5 percentage points of actual presidential vote shares, versus polling errors exceeding 1.9 points. Polymarket achieved a Brier score of 0.0581 across roughly 90,000 resolved predictions — a figure that places it "on par with the best prediction models in existence," according to analysts at Marginal Revolution. In corporate settings, Hewlett-Packard's internal prediction markets beat official sales forecasts six times out of eight. The pattern is consistent: when Hayek's conditions hold — diverse participants, decentralized knowledge, real stakes — the crowd outperforms the expert.

When the efficient market hypothesis meets its strangest test

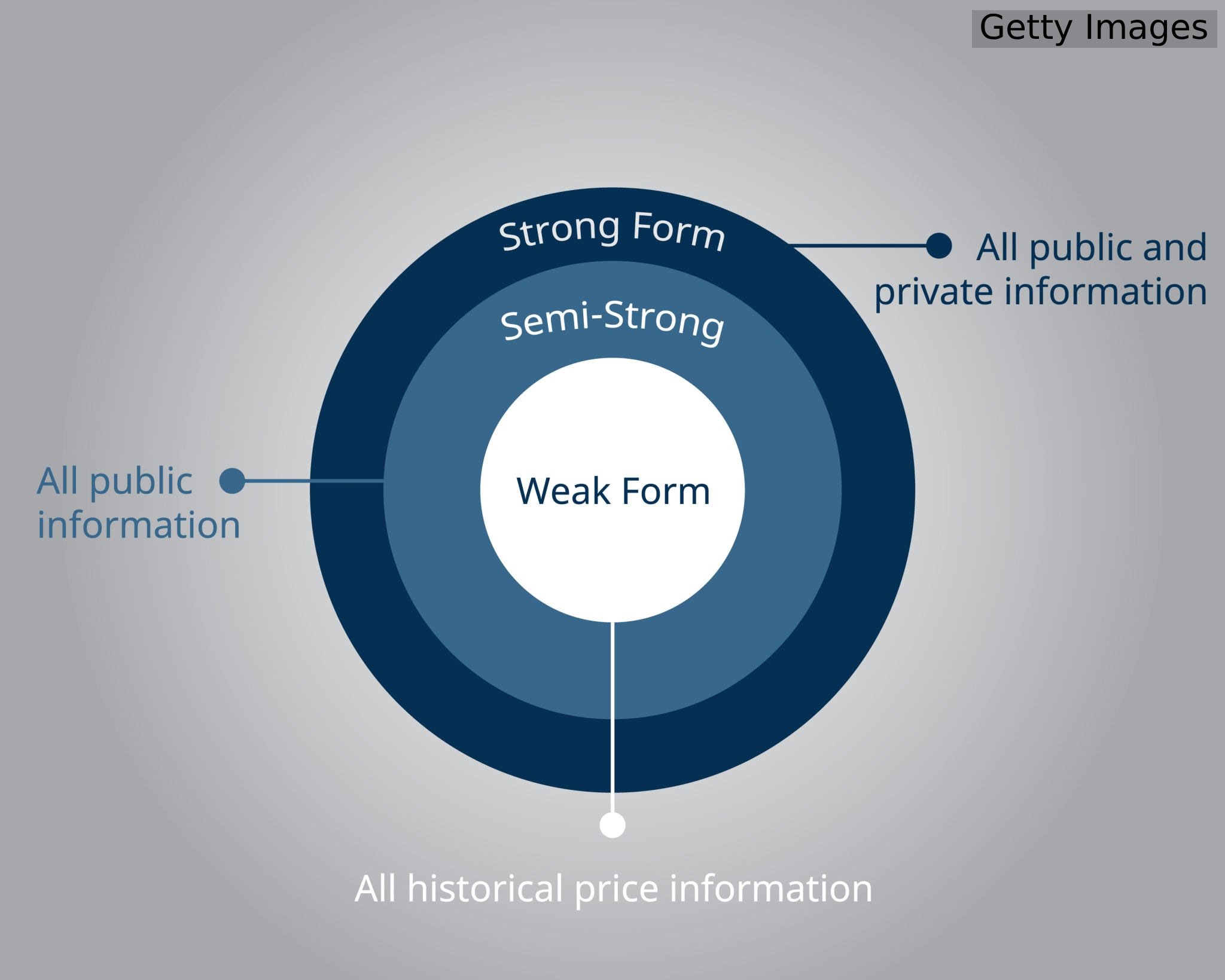

The Efficient Market Hypothesis holds that prices in competitive markets reflect all available information. Prediction markets test this proposition in a domain far removed from equities: the probability of discrete future events. Wolfers and Zitzewitz's foundational 2004 work in the Journal of Economic Perspectives demonstrated that under risk-neutrality assumptions, prediction market prices converge toward the mean belief among traders, producing an "efficient estimate of the true likelihood." Empirical tests largely confirm this — prediction market prices follow random walks, incorporate new information rapidly, and leave limited room for profitable trading strategies.

But the EMH's application to prediction markets reveals cracks that traditional finance can obscure. The favorite-longshot bias — a systematic tendency for bettors to overprice unlikely outcomes — is pronounced. Academic analysis of over 300,000 Kalshi contracts found that contracts priced below 10 cents lose investors more than 60% of their capital, while the average pre-fee return across all contracts sits at negative 20%. This is not a market failure in the aggregate; prices still convey useful information. It is, however, a wealth transfer mechanism operating with mathematical precision: sophisticated market makers extract consistent returns from retail participants who systematically overpay for longshots. The EMH tells us the price is right. It does not tell us who pays for it to be right.

The fine line between crowd wisdom and crowd madness

James Surowiecki's framework requires four conditions for collective intelligence: diversity of opinion, independence of judgment, decentralization, and a robust aggregation mechanism. Prediction markets satisfy all four — until they don't. The 2016 Brexit vote and U.S. presidential election represent canonical failures where herding behavior overwhelmed independent judgment, producing markets that reinforced prevailing elite consensus rather than aggregating dispersed signals.

Game theory illuminates why. In thin markets, a single actor can shift equilibrium prices. Polymarket's "French whale" — a trader operating under at least four accounts — wagered approximately $42–52 million on Trump outcomes, at one point holding over 20% of all "yes" shares on Trump winning. His profits reached an estimated $48–85 million. Agent-based simulations published in January 2026 by Oxford researchers confirmed the mechanism: "biased whales can temporarily shift prices, with the magnitude and duration of distortion increasing when non-whale bettors exhibit herding behavior." The strategic calculus is asymmetric. A well-capitalized actor faces bounded losses but can generate unbounded informational externalities — shaping media narratives, campaign donations, and voter expectations through the very prices that journalists now broadcast on CNN and CNBC as objective probabilities.

The counterargument, advanced by Robin Hanson and supported by historical evidence from Rhode and Strumpf's analysis of 19th-century betting markets, is that manipulation attempts are self-correcting. Manipulators create profit opportunities for informed traders who bet against them, ultimately thickening the market and improving accuracy. Hanson and colleagues found experimentally that manipulation "can end up increasing the accuracy of the market." The empirical record suggests both positions hold: manipulation distorts prices temporarily, but thick, liquid markets recover. The problem is that many prediction markets remain thin.

Who captures value and who absorbs risk

The distribution of costs and benefits in prediction markets reveals a counterintuitive structure. Society broadly captures the informational surplus — better forecasts of Fed decisions, election outcomes, hurricane paths, and pandemic trajectories. Corporate prediction markets have demonstrated measurable improvements in organizational decision-making. This is genuine public value.

The platforms capture fees efficiently. Kalshi generated an estimated $260 million in revenue in 2025 on approximately 1.2% of volume, while reaching an $11 billion valuation after raising over $1.5 billion. Polymarket, valued at $8–9 billion following a $2 billion investment from Intercontinental Exchange, has positioned itself as the Bloomberg terminal of event probabilities through partnerships with X, Yahoo Finance, and the NYSE.

Retail participants bear disproportionate risk. The favorite-longshot bias functions as a regressive tax on unsophisticated bettors. A Columbia University study found that roughly 25% of Polymarket's volume may constitute wash trading. Kalshi's sports contracts — representing 89% of its 2025 fee revenue — have drawn cease-and-desist orders from over a dozen states arguing these are functionally gambling products marketed as financial instruments. The National Council on Problem Gambling has flagged that Kalshi's minimum trading age of 18 sits below the 21-year threshold applied to sportsbooks, precisely targeting the demographic most vulnerable to gambling harms. A January 2026 paper in Addiction explicitly categorized prediction markets as "an emerging form of gambling" linked to "economic loss, mental health problems, and addiction."

The regulatory arbitrage is the quiet engine of the industry's growth. By operating under CFTC jurisdiction as derivatives exchanges rather than under state gaming commissions, Kalshi and Polymarket avoid state gambling taxes, responsible-gambling mandates, and self-exclusion requirements standard in sports betting. Federal courts have split on whether this preemption holds — New Jersey affirmed it, Maryland rejected it, Nevada reversed course — creating a legal patchwork that will likely require Supreme Court resolution.

The states strike back: "gambling — pure and simple"

The theoretical elegance of Hayekian price discovery has collided with a far more visceral political reality. As of February 2026, Kalshi faces 19 federal lawsuits across various stages, all grappling with a single definitional question: does placing monetary wagers on sports events constitute a type of game? The battle lines pit federal preemption — the argument that CFTC jurisdiction over designated contract markets supersedes state authority — against the states' centuries-old regulatory power over gambling.

Nevada's effort to block Kalshi is the most closely watched case, carrying outsized symbolic weight. Long before the Supreme Court cleared the way for states to legalize sports gambling in 2018, Nevada stood as the nation's sole legal purveyor of sports betting — and its Gaming Control Board is treating prediction markets as an existential threat. A district court judge sided with Nevada in the Crypto.com case, and the matter is now before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. Massachusetts delivered an even sharper blow: in January 2026, a Superior Court judge issued a preliminary injunction against Kalshi, effectively banning the platform from offering sports-based betting within the state, calling the company's federal preemption argument "overly broad." Kalshi warned that an injunction could force the halting or liquidation of $650 million in contracts.

The Trump administration has weighed in decisively on the industry's side. CFTC Chairman Michael Selig filed a friend-of-the-court brief supporting Crypto.com in Nevada — the first time under his leadership that the CFTC has taken sides in the regulatory battle. His framing was unambiguous: the CFTC characterized event contracts as "swaps" — derivative instruments under the Commodity Exchange Act — and argued it would no longer allow "overzealous state governments" to undermine the agency's exclusive jurisdiction. President Trump's son, Donald Trump Jr., serves as both an investor in Polymarket and a strategic advisor for Kalshi, adding a layer of political entanglement that critics argue undermines the CFTC's regulatory independence.

The backlash was immediate and bipartisan in character. Utah Governor Spencer Cox responded directly on X, vowing to use "every resource" to fight the CFTC and calling prediction markets "gambling — pure and simple" that are "destroying the lives of families and countless Americans, especially young men." Over the summer of 2025, 60 tribes, 34 state regulators, and nine tribal groups filed amicus briefs supporting state authority. The coalition reflects an unusual convergence of interests: tribal gaming operators protecting sovereign revenue streams, state regulators defending licensing frameworks, and public health advocates alarmed by a product that allows 18-year-olds to place live, second-by-second wagers in states where sports betting is otherwise illegal.

The game-theoretic structure of this regulatory battle is itself instructive. Prediction market operators face a classic coordination problem: they need a single federal rulebook to achieve the scale their business models require, but each state has independent incentive to defect from federal preemption to protect local tax revenue, tribal compacts, and regulatory authority. TD Cowen's Washington Research Group gave a "slight edge to the states," noting that this Supreme Court "appears to give weight to historical precedents" — and the historical precedent here is unambiguous state authority over gambling. Analysts estimate the legal stalling could extend through 2028, creating a protracted period of regulatory uncertainty that paradoxically benefits incumbents while deterring new entrants.

The conflict also exposes the prediction market industry's fundamental identity crisis. The Massachusetts Attorney General's office noted that Kalshi's "event contracts" include moneyline contracts, point spread contracts, and over-under contracts that "closely resemble sports wagers offered by licensed operators." Sports-related activity now constitutes more than 90% of site activity and 89% of Kalshi's 2025 revenue. The platform that built its intellectual credibility on Hayekian information aggregation derives the vast majority of its income from what state regulators — and increasingly, federal courts — recognize as sports betting by another name. As Ohio's First Assistant Attorney General put it: "Sports contracts and pork bellies aren't the same." The question heading to the Supreme Court is not whether prediction markets produce valuable information. It is whether the industry that Hayek inspired has become something Hayek never envisioned — a nationwide sports gambling operation wearing the regulatory clothes of a commodity exchange.

Conclusion: the information is real, but so are the costs

Prediction markets represent perhaps the most elegant real-world implementation of Hayekian price theory ever constructed. Their informational accuracy — validated across elections, economic indicators, and corporate forecasting — is not seriously in dispute. The harder question is distributive. The same mechanism that produces superior forecasts systematically transfers wealth from less-informed to more-informed participants, creates manipulation vectors in thin markets that can distort democratic discourse, and packages what behavioral research increasingly identifies as gambling products under the regulatory framework of commodity derivatives. The $44 billion flowing through these markets in 2025 purchased genuinely valuable information for society. The invoice, as usual in economics, was sent to those least equipped to read the fine print.